Class act: SKF gains third approval for CBM services

17 Oct,2018

Ship operators need to know that their CBM service provider is up to the job – which is why it is vital to use a class-approved supplier

Condition-based maintenance (CBM) is a technique that proactively monitors and reports on the condition of machinery and its components. While the manufacturing industry has embraced CBM, it is still in its relative infancy in the maritime sector.

The goals of maritime industry are similar to those in manufacturing: improving maintenance, boosting uptime, controlling cost. In the past inherent technical constraints such as limited internet connectivity, while adhering to the stringent rules and regulations, has held back wider adoption of CBM within the maritime sector. However, this is beginning to change as the industry recognises the benefits of a maintenance regime that identifies faults as they happen – allowing them to be fixed before they escalate into major problems.

Operators need to be confident that any CBM system they adopt will be installed properly, work with minimal intervention, and not contravene any local or global regulations. This is achieved if the system is installed and run by a class-approved supplier.

Class approval

International classification societies like DNV GL, Lloyd’s Register and ABS ensure that ships and offshore structures achieve certain levels of quality and reliability. They check and approve the design, materials, and components of newly built vessels and periodically inspect ships in operation to verify that standards are maintained – and, if they are, the operator receives the classification certificate, which typically lasts five years.

As more ship operators begin to implement CBM strategies, classification societies have adapted their rules and regulations in order to certify CBM for use on ships. One element of this is to ensure that onboard condition monitoring systems deliver accurate information. If the systems are not monitoring correctly, the crew could draw false conclusions from the data – which could jeopardise the reliability of a ship. For this reason, service suppliers must prove that they can meet specified high standards before they are permitted to work with approved vessels.

Suppliers of CBM systems will argue that theirs can be applied to the maritime industry. This may be true in theory – but they must first gain class approval. Without DNV GL class approval, for instance, a CBM system cannot be used on a DNV GL-approved ship.

SKF, for instance, has received class approval for its CBM services from DNV GL. It is SKF’s third such class approval in CBM, as it also has earlier accreditations from Lloyd’s Register and ABS.

Quality standards

To gain class approval, a service supplier must first prove it can carry out its services at a consistently high standard of quality. Classification societies verify that CBM systems are installed properly, that they are collecting the right amount of information to form an accurate picture, and that the data is analysed by qualified, skilled personnel.

This is a vital element: CBM is about more than just the hardware and data collection – and extends to the interpretation of the data. This is increasingly done by remote experts, who know exactly how to analyse the data and give recommendations based on what it reveals.

Classification societies also insist that suppliers have a continuous improvement programme in place, which includes training. If they can do all this, they receive certification that is valid for three years.

CBM benefits

Shipbuilders, like other manufacturers, are under intense cost pressure, while ship owners are striving to make their operations as lean as possible. They must minimise cost – by cutting down on crew numbers, for example – in order to boost profitability. While CBM might seem an expensive luxury, investing in it can produce cost savings – whether by trimming the number of on-board staff, boosting fuel efficiency or reducing the need for major repairs and related downtime.

The early adopters of CBM will be the highest value vessels and those used in the oil and gas industry. A ship used in the oil and gas industry is typically brought into dry dock every 2.5 years for a complete overhaul of on-board machinery. By keeping a constant watch on all on-board machinery, automated CBM could delay the need for major overhaul – meaning that a ship will undergo fewer major maintenance operations during its lifetime. Planned repairs can also be carried out with more confidence.

SKF has been supplying CBM to the maritime industry for nearly 10 years, and has a deep knowledge about the optimum conditions of all relevant marine components, especially bearings.

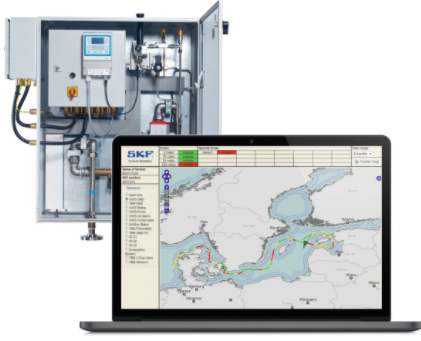

Beyond maintenance, CBM is beginning to encompass performance monitoring – as ship owners must collect a vast array of information such as fuel consumption and emission levels. Using systems such as SKF BlueMon – an environmental monitoring system that records everything in one place – is an effective way of doing this. By linking to GPS position data, it helps compliance with relevant regulations: if a ship is approaching an area with higher emission standards, for instance, a warning can be sent to the bridge so that emission levels can be re-checked. This type of system – which effectively fills in the ship’s logbook automatically – is likely to become far more common in future.

Boosting trust

At the end of the day, class approvals establish trust between shipping companies, operators, and suppliers. If a ship operator works with, say, a DNV GL-approved service supplier, it knows that DNV GL has checked and verified everything in detail – so it can rely on the data from its condition monitoring systems.

For some applications, implementing these systems will extend the standard survey interval of five years – and sometimes even the manufacturer’s recommendations for periodic maintenance. There can be other stipulations: those supplying services into the oil and gas sector, for instance, may be required to have class approval simply in order to bid for a contract.

While the end users – such as ship builders and operators – derive the main advantage from class approval, it is also of huge benefit to the service suppliers themselves. During the process, suppliers receive guidance on how to comply with the requirements – and as a result, are likely to identify multiple ways to improve what they do. They can therefore enhance the quality of their services during the process.

In SKF’s recent example, gaining class approval from DNV GL was an 18-month process: this was a major investment of time and money, but one that has made its CBM services available to a far wider range of customers.